The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement, published in 2009, was designed to help systematic reviewers transparently report why the review was done, what the authors did, and what they found. Over the past decade, advances in systematic review methodology and terminology have necessitated an update to the guideline. The PRISMA 2020 statement replaces the 2009 statement and includes new reporting guidance that reflects advances in methods to identify, select, appraise, and synthesise studies. The structure and presentation of the items have been modified to facilitate implementation. In this article, we present the PRISMA 2020 27-item checklist, an expanded checklist that details reporting recommendations for each item, the PRISMA 2020 abstract checklist, and the revised flow diagrams for original and updated reviews. In order to encourage its wide dissemination this article is freely accessible on BMJ, PLOS Medicine, Journal of Clinical Epidemiology and International Journal of Surgery journal websites.

Systematic reviews serve many critical roles. They can provide syntheses of the state of knowledge in a field, from which future research priorities can be identified; they can address questions that otherwise could not be answered by individual studies; they can identify problems in primary research that should be rectified in future studies; and they can generate or evaluate theories about how or why phenomena occur. Systematic reviews therefore generate various types of knowledge for different users of reviews (such as patients, healthcare providers, researchers, and policy makers) [1, 2]. To ensure a systematic review is valuable to users, authors should prepare a transparent, complete, and accurate account of why the review was done, what they did (such as how studies were identified and selected) and what they found (such as characteristics of contributing studies and results of meta-analyses). Up-to-date reporting guidance facilitates authors achieving this [3].

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement published in 2009 (hereafter referred to as PRISMA 2009) [4,5,6,7,8,9,10] is a reporting guideline designed to address poor reporting of systematic reviews [11]. The PRISMA 2009 statement comprised a checklist of 27 items recommended for reporting in systematic reviews and an “explanation and elaboration” paper [12,13,14,15,16] providing additional reporting guidance for each item, along with exemplars of reporting. The recommendations have been widely endorsed and adopted, as evidenced by its co-publication in multiple journals, citation in over 60,000 reports (Scopus, August 2020), endorsement from almost 200 journals and systematic review organisations, and adoption in various disciplines. Evidence from observational studies suggests that use of the PRISMA 2009 statement is associated with more complete reporting of systematic reviews [17,18,19,20], although more could be done to improve adherence to the guideline [21].

Many innovations in the conduct of systematic reviews have occurred since publication of the PRISMA 2009 statement. For example, technological advances have enabled the use of natural language processing and machine learning to identify relevant evidence [22,23,24], methods have been proposed to synthesise and present findings when meta-analysis is not possible or appropriate [25,26,27], and new methods have been developed to assess the risk of bias in results of included studies [28, 29]. Evidence on sources of bias in systematic reviews has accrued, culminating in the development of new tools to appraise the conduct of systematic reviews [30, 31]. Terminology used to describe particular review processes has also evolved, as in the shift from assessing “quality” to assessing “certainty” in the body of evidence [32]. In addition, the publishing landscape has transformed, with multiple avenues now available for registering and disseminating systematic review protocols [33, 34], disseminating reports of systematic reviews, and sharing data and materials, such as preprint servers and publicly accessible repositories. To capture these advances in the reporting of systematic reviews necessitated an update to the PRISMA 2009 statement.

Summary points

• To ensure a systematic review is valuable to users, authors should prepare a transparent, complete, and accurate account of why the review was done, what they did, and what they found

• The PRISMA 2020 statement provides updated reporting guidance for systematic reviews that reflects advances in methods to identify, select, appraise, and synthesise studies

• The PRISMA 2020 statement consists of a 27-item checklist, an expanded checklist that details reporting recommendations for each item, the PRISMA 2020 abstract checklist, and revised flow diagrams for original and updated reviews

• We anticipate that the PRISMA 2020 statement will benefit authors, editors, and peer reviewers of systematic reviews, and different users of reviews, including guideline developers, policy makers, healthcare providers, patients, and other stakeholders

A complete description of the methods used to develop PRISMA 2020 is available elsewhere [35]. We identified PRISMA 2009 items that were often reported incompletely by examining the results of studies investigating the transparency of reporting of published reviews [17, 21, 36, 37]. We identified possible modifications to the PRISMA 2009 statement by reviewing 60 documents providing reporting guidance for systematic reviews (including reporting guidelines, handbooks, tools, and meta-research studies) [38]. These reviews of the literature were used to inform the content of a survey with suggested possible modifications to the 27 items in PRISMA 2009 and possible additional items. Respondents were asked whether they believed we should keep each PRISMA 2009 item as is, modify it, or remove it, and whether we should add each additional item. Systematic review methodologists and journal editors were invited to complete the online survey (110 of 220 invited responded). We discussed proposed content and wording of the PRISMA 2020 statement, as informed by the review and survey results, at a 21-member, two-day, in-person meeting in September 2018 in Edinburgh, Scotland. Throughout 2019 and 2020, we circulated an initial draft and five revisions of the checklist and explanation and elaboration paper to co-authors for feedback. In April 2020, we invited 22 systematic reviewers who had expressed interest in providing feedback on the PRISMA 2020 checklist to share their views (via an online survey) on the layout and terminology used in a preliminary version of the checklist. Feedback was received from 15 individuals and considered by the first author, and any revisions deemed necessary were incorporated before the final version was approved and endorsed by all co-authors.

The PRISMA 2020 statement has been designed primarily for systematic reviews of studies that evaluate the effects of health interventions, irrespective of the design of the included studies. However, the checklist items are applicable to reports of systematic reviews evaluating other interventions (such as social or educational interventions), and many items are applicable to systematic reviews with objectives other than evaluating interventions (such as evaluating aetiology, prevalence, or prognosis). PRISMA 2020 is intended for use in systematic reviews that include synthesis (such as pairwise meta-analysis or other statistical synthesis methods) or do not include synthesis (for example, because only one eligible study is identified). The PRISMA 2020 items are relevant for mixed-methods systematic reviews (which include quantitative and qualitative studies), but reporting guidelines addressing the presentation and synthesis of qualitative data should also be consulted [39, 40]. PRISMA 2020 can be used for original systematic reviews, updated systematic reviews, or continually updated (“living”) systematic reviews. However, for updated and living systematic reviews, there may be some additional considerations that need to be addressed. Where there is relevant content from other reporting guidelines, we reference these guidelines within the items in the explanation and elaboration paper [41] (such as PRISMA-Search [42] in items 6 and 7, Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) reporting guideline [27] in item 13d). Box 1 includes a glossary of terms used throughout the PRISMA 2020 statement.

PRISMA 2020 is not intended to guide systematic review conduct, for which comprehensive resources are available [43,44,45,46]. However, familiarity with PRISMA 2020 is useful when planning and conducting systematic reviews to ensure that all recommended information is captured. PRISMA 2020 should not be used to assess the conduct or methodological quality of systematic reviews; other tools exist for this purpose [30, 31]. Furthermore, PRISMA 2020 is not intended to inform the reporting of systematic review protocols, for which a separate statement is available (PRISMA for Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement [47, 48]). Finally, extensions to the PRISMA 2009 statement have been developed to guide reporting of network meta-analyses [49], meta-analyses of individual participant data [50], systematic reviews of harms [51], systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy studies [52], and scoping reviews [53]; for these types of reviews we recommend authors report their review in accordance with the recommendations in PRISMA 2020 along with the guidance specific to the extension.

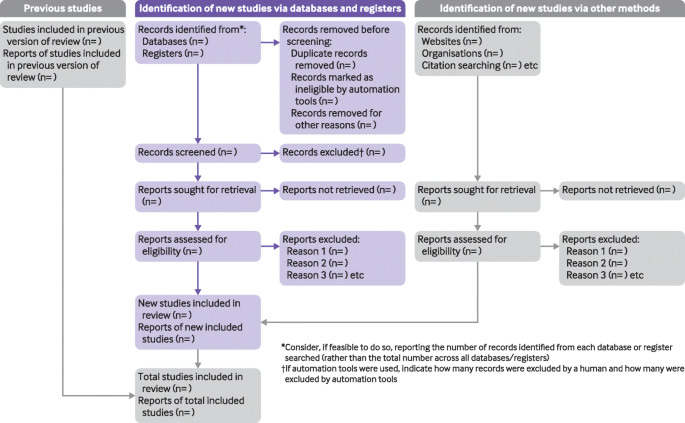

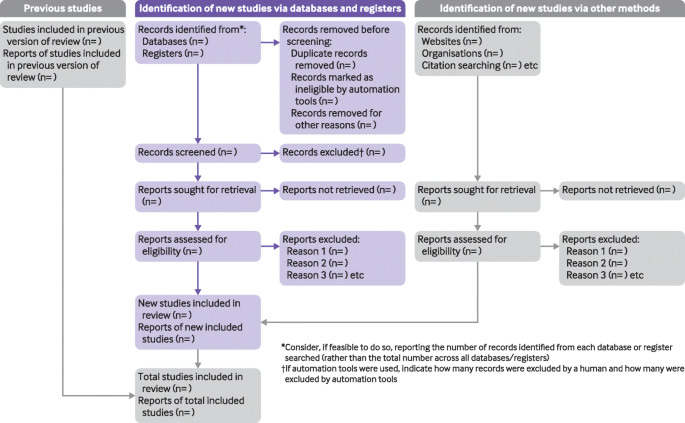

The PRISMA 2020 statement (including the checklists, explanation and elaboration, and flow diagram) replaces the PRISMA 2009 statement, which should no longer be used. Box 2 summarises noteworthy changes from the PRISMA 2009 statement. The PRISMA 2020 checklist includes seven sections with 27 items, some of which include sub-items (Table 1). A checklist for journal and conference abstracts for systematic reviews is included in PRISMA 2020. This abstract checklist is an update of the 2013 PRISMA for Abstracts statement [54], reflecting new and modified content in PRISMA 2020 (Table 2). A template PRISMA flow diagram is provided, which can be modified depending on whether the systematic review is original or updated (Fig. 1).

We recommend authors refer to PRISMA 2020 early in the writing process, because prospective consideration of the items may help to ensure that all the items are addressed. To help keep track of which items have been reported, the PRISMA statement website (http://www.prisma-statement.org/) includes fillable templates of the checklists to download and complete (also available in Additional file 1). We have also created a web application that allows users to complete the checklist via a user-friendly interface [58] (available at https://prisma.shinyapps.io/checklist/ and adapted from the Transparency Checklist app [59]). The completed checklist can be exported to Word or PDF. Editable templates of the flow diagram can also be downloaded from the PRISMA statement website.

We have prepared an updated explanation and elaboration paper, in which we explain why reporting of each item is recommended and present bullet points that detail the reporting recommendations (which we refer to as elements) [41]. The bullet-point structure is new to PRISMA 2020 and has been adopted to facilitate implementation of the guidance [60, 61]. An expanded checklist, which comprises an abridged version of the elements presented in the explanation and elaboration paper, with references and some examples removed, is available in Additional file 2. Consulting the explanation and elaboration paper is recommended if further clarity or information is required.

Journals and publishers might impose word and section limits, and limits on the number of tables and figures allowed in the main report. In such cases, if the relevant information for some items already appears in a publicly accessible review protocol, referring to the protocol may suffice. Alternatively, placing detailed descriptions of the methods used or additional results (such as for less critical outcomes) in supplementary files is recommended. Ideally, supplementary files should be deposited to a general-purpose or institutional open-access repository that provides free and permanent access to the material (such as Open Science Framework, Dryad, figshare). A reference or link to the additional information should be included in the main report. Finally, although PRISMA 2020 provides a template for where information might be located, the suggested location should not be seen as prescriptive; the guiding principle is to ensure the information is reported.

Use of PRISMA 2020 has the potential to benefit many stakeholders. Complete reporting allows readers to assess the appropriateness of the methods, and therefore the trustworthiness of the findings. Presenting and summarising characteristics of studies contributing to a synthesis allows healthcare providers and policy makers to evaluate the applicability of the findings to their setting. Describing the certainty in the body of evidence for an outcome and the implications of findings should help policy makers, managers, and other decision makers formulate appropriate recommendations for practice or policy. Complete reporting of all PRISMA 2020 items also facilitates replication and review updates, as well as inclusion of systematic reviews in overviews (of systematic reviews) and guidelines, so teams can leverage work that is already done and decrease research waste [36, 62, 63].

We updated the PRISMA 2009 statement by adapting the EQUATOR Network’s guidance for developing health research reporting guidelines [64]. We evaluated the reporting completeness of published systematic reviews [17, 21, 36, 37], reviewed the items included in other documents providing guidance for systematic reviews [38], surveyed systematic review methodologists and journal editors for their views on how to revise the original PRISMA statement [35], discussed the findings at an in-person meeting, and prepared this document through an iterative process. Our recommendations are informed by the reviews and survey conducted before the in-person meeting, theoretical considerations about which items facilitate replication and help users assess the risk of bias and applicability of systematic reviews, and co-authors’ experience with authoring and using systematic reviews.

Various strategies to increase the use of reporting guidelines and improve reporting have been proposed. They include educators introducing reporting guidelines into graduate curricula to promote good reporting habits of early career scientists [65]; journal editors and regulators endorsing use of reporting guidelines [18]; peer reviewers evaluating adherence to reporting guidelines [61, 66]; journals requiring authors to indicate where in their manuscript they have adhered to each reporting item [67]; and authors using online writing tools that prompt complete reporting at the writing stage [60]. Multi-pronged interventions, where more than one of these strategies are combined, may be more effective (such as completion of checklists coupled with editorial checks) [68]. However, of 31 interventions proposed to increase adherence to reporting guidelines, the effects of only 11 have been evaluated, mostly in observational studies at high risk of bias due to confounding [69]. It is therefore unclear which strategies should be used. Future research might explore barriers and facilitators to the use of PRISMA 2020 by authors, editors, and peer reviewers, designing interventions that address the identified barriers, and evaluating those interventions using randomised trials. To inform possible revisions to the guideline, it would also be valuable to conduct think-aloud studies [70] to understand how systematic reviewers interpret the items, and reliability studies to identify items where there is varied interpretation of the items.

We encourage readers to submit evidence that informs any of the recommendations in PRISMA 2020 (via the PRISMA statement website: http://www.prisma-statement.org/). To enhance accessibility of PRISMA 2020, several translations of the guideline are under way (see available translations at the PRISMA statement website). We encourage journal editors and publishers to raise awareness of PRISMA 2020 (for example, by referring to it in journal “Instructions to authors”), endorsing its use, advising editors and peer reviewers to evaluate submitted systematic reviews against the PRISMA 2020 checklists, and making changes to journal policies to accommodate the new reporting recommendations. We recommend existing PRISMA extensions [47, 49,50,51,52,53, 71, 72] be updated to reflect PRISMA 2020 and advise developers of new PRISMA extensions to use PRISMA 2020 as the foundation document.

We anticipate that the PRISMA 2020 statement will benefit authors, editors, and peer reviewers of systematic reviews, and different users of reviews, including guideline developers, policy makers, healthcare providers, patients, and other stakeholders. Ultimately, we hope that uptake of the guideline will lead to more transparent, complete, and accurate reporting of systematic reviews, thus facilitating evidence based decision making.

Systematic review—A review that uses explicit, systematic methods to collate and synthesise findings of studies that address a clearly formulated question [43]

Statistical synthesis—The combination of quantitative results of two or more studies. This encompasses meta-analysis of effect estimates (described below) and other methods, such as combining P values, calculating the range and distribution of observed effects, and vote counting based on the direction of effect (see McKenzie and Brennan [25] for a description of each method)

Meta-analysis of effect estimates—A statistical technique used to synthesise results when study effect estimates and their variances are available, yielding a quantitative summary of results [25]

Outcome—An event or measurement collected for participants in a study (such as quality of life, mortality)

Result—The combination of a point estimate (such as a mean difference, risk ratio, or proportion) and a measure of its precision (such as a confidence/credible interval) for a particular outcome

Report—A document (paper or electronic) supplying information about a particular study. It could be a journal article, preprint, conference abstract, study register entry, clinical study report, dissertation, unpublished manuscript, government report, or any other document providing relevant information

Record—The title or abstract (or both) of a report indexed in a database or website (such as a title or abstract for an article indexed in Medline). Records that refer to the same report (such as the same journal article) are “duplicates”; however, records that refer to reports that are merely similar (such as a similar abstract submitted to two different conferences) should be considered unique.

Study—An investigation, such as a clinical trial, that includes a defined group of participants and one or more interventions and outcomes. A “study” might have multiple reports. For example, reports could include the protocol, statistical analysis plan, baseline characteristics, results for the primary outcome, results for harms, results for secondary outcomes, and results for additional mediator and moderator analyses

• Inclusion of the abstract reporting checklist within PRISMA 2020 (see item #2 and Box 2).

• Movement of the ‘Protocol and registration’ item from the start of the Methods section of the checklist to a new Other section, with addition of a sub-item recommending authors describe amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol (see item #24a-24c).

• Modification of the ‘Search’ item to recommend authors present full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites searched, not just at least one database (see item #7).

• Modification of the ‘Study selection’ item in the Methods section to emphasise the reporting of how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process (see item #8).

• Addition of a sub-item to the ‘Data items’ item recommending authors report how outcomes were defined, which results were sought, and methods for selecting a subset of results from included studies (see item #10a).

• Splitting of the ‘Synthesis of results’ item in the Methods section into six sub-items recommending authors describe: the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis; any methods required to prepare the data for synthesis; any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses; any methods used to synthesise results; any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (such as subgroup analysis, meta-regression); and any sensitivity analyses used to assess robustness of the synthesised results (see item #13a-13f).

• Addition of a sub-item to the ‘Study selection’ item in the Results section recommending authors cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded (see item #16b).

• Splitting of the ‘Synthesis of results’ item in the Results section into four sub-items recommending authors: briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among studies contributing to the synthesis; present results of all statistical syntheses conducted; present results of any investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results; and present results of any sensitivity analyses (see item #20a-20d).

• Addition of new items recommending authors report methods for and results of an assessment of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome (see items #15 and #22).

• Addition of a new item recommending authors declare any competing interests (see item #26).

• Addition of a new item recommending authors indicate whether data, analytic code and other materials used in the review are publicly available and if so, where they can be found (see item #27).

We dedicate this paper to the late Douglas G Altman and Alessandro Liberati, whose contributions were fundamental to the development and implementation of the original PRISMA statement.

We thank the following contributors who completed the survey to inform discussions at the development meeting: Xavier Armoiry, Edoardo Aromataris, Ana Patricia Ayala, Ethan M Balk, Virginia Barbour, Elaine Beller, Jesse A Berlin, Lisa Bero, Zhao-Xiang Bian, Jean Joel Bigna, Ferrán Catalá-López, Anna Chaimani, Mike Clarke, Tammy Clifford, Ioana A Cristea, Miranda Cumpston, Sofia Dias, Corinna Dressler, Ivan D Florez, Joel J Gagnier, Chantelle Garritty, Long Ge, Davina Ghersi, Sean Grant, Gordon Guyatt, Neal R Haddaway, Julian PT Higgins, Sally Hopewell, Brian Hutton, Jamie J Kirkham, Jos Kleijnen, Julia Koricheva, Joey SW Kwong, Toby J Lasserson, Julia H Littell, Yoon K Loke, Malcolm R Macleod, Chris G Maher, Ana Marušic, Dimitris Mavridis, Jessie McGowan, Matthew DF McInnes, Philippa Middleton, Karel G Moons, Zachary Munn, Jane Noyes, Barbara Nußbaumer-Streit, Donald L Patrick, Tatiana Pereira-Cenci, Ba′ Pham, Bob Phillips, Dawid Pieper, Michelle Pollock, Daniel S Quintana, Drummond Rennie, Melissa L Rethlefsen, Hannah R Rothstein, Maroeska M Rovers, Rebecca Ryan, Georgia Salanti, Ian J Saldanha, Margaret Sampson, Nancy Santesso, Rafael Sarkis-Onofre, Jelena Savović, Christopher H Schmid, Kenneth F Schulz, Guido Schwarzer, Beverley J Shea, Paul G Shekelle, Farhad Shokraneh, Mark Simmonds, Nicole Skoetz, Sharon E Straus, Anneliese Synnot, Emily E Tanner-Smith, Brett D Thombs, Hilary Thomson, Alexander Tsertsvadze, Peter Tugwell, Tari Turner, Lesley Uttley, Jeffrey C Valentine, Matt Vassar, Areti Angeliki Veroniki, Meera Viswanathan, Cole Wayant, Paul Whaley, and Kehu Yang. We thank the following contributors who provided feedback on a preliminary version of the PRISMA 2020 checklist: Jo Abbott, Fionn Büttner, Patricia Correia-Santos, Victoria Freeman, Emily A Hennessy, Rakibul Islam, Amalia (Emily) Karahalios, Kasper Krommes, Andreas Lundh, Dafne Port Nascimento, Davina Robson, Catherine Schenck-Yglesias, Mary M Scott, Sarah Tanveer and Pavel Zhelnov. We thank Abigail H Goben, Melissa L Rethlefsen, Tanja Rombey, Anna Scott, and Farhad Shokraneh for their helpful comments on the preprints of the PRISMA 2020 papers. We thank Edoardo Aromataris, Stephanie Chang, Toby Lasserson and David Schriger for their helpful peer review comments on the PRISMA 2020 papers.

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patients and the public were not involved in this methodological research. We plan to disseminate the research widely, including to community participants in evidence synthesis organisations.

There was no direct funding for this research. MJP is supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE200101618) and was previously supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Early Career Fellowship (1088535) during the conduct of this research. JEM is supported by an Australian NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (1143429). TCH is supported by an Australian NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (1154607). JMT is supported by Evidence Partners Inc. JMG is supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Health Knowledge Transfer and Uptake. MML is supported by The Ottawa Hospital Anaesthesia Alternate Funds Association and a Faculty of Medicine Junior Research Chair. TL is supported by funding from the National Eye Institute (UG1EY020522), National Institutes of Health, United States. LAM is supported by a National Institute for Health Research Doctoral Research Fellowship (DRF-2018-11-ST2–048). ACT is supported by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Synthesis. DM is supported in part by a University Research Chair, University of Ottawa. The funders had no role in considering the study design or in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.