My 42-page summary of contracts law, updated in 2019, is below. Here are the links to my Contracts diagrams:

I highly recommend Understanding Contracts by Jeffrey T. Ferriell. Like the other books in the Understanding series, this volume provides a clear and concise explanation of the law. I referred to it regularly in studying for the bar exam and in creating these diagrams, and as usual, I learned much more from the Understanding book than I did from my casebook. You can click on the image to take advantage of Amazon’s Look Inside feature and start reading.

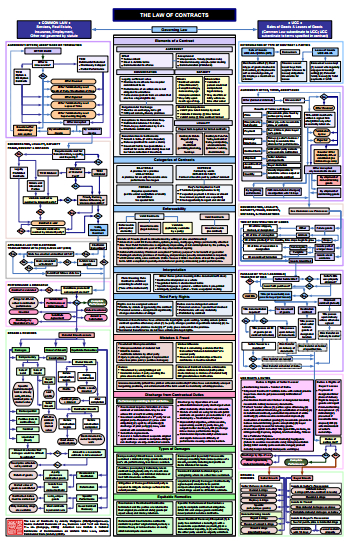

I also recently came across a very detailed Contracts flowchart by Jeremy Modjeska that may be helpful to you. Click the image below to visit his site and view the chart.

My summary of contracts law is available as a downloadable PDF and as text below. When viewing the PDF on a computer, you can navigate by clicking on entries in the table of contents and on page headings.

On the Uniform Bar Exam, test takers are to assume that the Official Text of Articles 1 and 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code is in effect. All contracts involving the sale of goods are governed by Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code. One’s first question upon being presented with a fact pattern should be, “Does this contract involve the sale of goods?” If so, look to the UCC for the law. “Goods” include all movable, tangible goods, not real estate, and not intellectual property. UCC rules do not differ greatly from common law rules, but they do differ. In UCC cases, common law principles may still be applied in interpreting the law.

Some transactions involve both the sale of goods and the sale of services. Courts will apply one of two tests to determine whether UCC or common law rules apply to the case:

Predominant purpose test: In this, the more common test, a court will determine what the predominant purpose of the contract is. If I have washed and detailed your car, the contract was primarily one for the sale of my services to you; the small amount of sealant that I applied to the car is technically a good that I sold to you, but that sale was not the predominant purpose of the contract. In this example, if this test is used, the court will apply common law rules to the case.

Gravamen test: Courts will sometimes apply this test, in which they determine what the conflict is primarily about. If the sealant I used on your car caused the paint to peel away, then the gravamen of the case is that good that I sold to you. In this example, if this test is used, the court will apply UCC rules to the case.

A contract exists when two or more parties agree on promises to exchange things of value. Every contract must include a valid offer, acceptance, and consideration. The offer represents the content of the agreement, the acceptance represents the fact of agreement itself, and the consideration represents the exchange of value.

The offer represents the content of the agreement. For example, the offeror may say, “I’ll sell you this car for one thousand dollars.”

The offer also conveys power of acceptance to the offeree. In the example above, the offeree may simply say, “It’s a deal.” The offeree has exercised the power of acceptance conveyed to them by the offeror, and they have created a contract.

A valid offer must contain clear and definite terms and must convey power of acceptance to the offeree.

Clear and definite terms: A valid offer contains clear and definite terms. To determine this, a common analytical device is the acronym QTIPS:

In the classical model, the offer contains all of the above, and the acceptance is merely an expression of assent. There are many exceptions to this, but before addressing them, one must analyze an offer for clear and definite terms, and weigh the importance of their inclusion or omission. For instance, the omission of time for the contract to be performed will usually not make an offer invalid. Our example above does not indicate when the car will be delivered or when the thousand dollars will be paid. But the offeree’s statement, “It’s a deal,” still forms a valid contract. Missing terms will be filled in by what is determined to be reasonable. If the offeror refuses to sell the car, their claim that they meant that they would sell the car five years from now, will not be judged to be reasonable.

Other terms, such as price and quantity, are more important. Courts are more likely to fill in a “reasonable” price when the contract is for the sale of fungible goods, less likely when it is for unique goods.

Conveyance of power of acceptance: A valid offer conveys power of acceptance to the offeree. In other words, a simple expression of assent by the offeree will conclude the bargain. The statement, “I would like to consider selling you my car for a thousand dollars, but first I need to sleep on it,” does not convey power of acceptance to the person addressed, because it contains conditional language. To say in response, “It’s a deal,” creates no legal obligations, but merely acknowledges that further negotiation may take place in the future.

An offer made in jest: An offer which the offeree knows or should know is made in jest is not a valid offer.

Preliminary negotiations and statements of future intentions: “I’m thinking of selling my car for a thousand dollars,” or “I am going to sell my car for a thousand dollars.”

Price quotations: Generally, a price quote is not an offer, especially if it does not include a quantity, is not addressed to a particular offeree, or does not include words like “offer.”

Solicitations of offers: One must often determine whether a proposal is a solicitation of an offer, or an offer, especially in the case of advertisements. An example of a solicitation would be, “I would like to sell you my car. Make me an offer.” Solicitations create no legal obligations. Advertisements will normally be construed by courts to be invitations to the public to make offers. However, an advertisement may be construed to be an offer if it would lead a reasonable prospective buyer to believe that an offer was intended. This would be so if the advertisement contains the elements of an offer: clear and definite terms, and apparent conveyance of power of acceptance to the offeree. Putting an item up for auction is a solicitation of offers.

UCC rules may mirror common law rules, or they may be quite different. In the realm of the offer, the UCC differs in that less emphasis is placed on identifying the offer and acceptance as separate elements.

UCC section 2-204 states that a contract may be made in any manner sufficient to show agreement, including conduct by the parties; a contract may be found even though the moment of its making is undetermined; and a contract will not fail for indefiniteness even though one or more terms are left open, as long as the parties intended to make a contract and there is a reasonable basis for a remedy.

The acceptance is the offeree’s manifestation of assent. It represents agreement, and it creates the contract. To be valid, the acceptance must be knowing, voluntary, and deliberate. In determining whether a valid acceptance has been made, the proper focus is on whether a reasonable offeror would understand that the offeree had accepted. As with the analysis of the offer, this is the objective, or “reasonable person” test. In other words, it does not matter what the offeror and offeree actually intended their words or actions to mean (the subjective test), it matters how a reasonable person would have interpreted them.

Communication to the offeror: When communication is instantaneous, such as face-to-face or by telephone, a cceptance is valid when it is received by the offeror. W hen the communication is through the mail or by another means that involves a time delay, then the mailbox rule applies, and acceptance is valid upon dispatch. However, there is an exception for option contract s: acceptance is valid upon receipt, not upon dispatch.

Accord with the substantive terms of the offer: The acceptance must be in accord with the substantive terms and the procedural requirements of the offer. Regarding substantive terms, responding to, “I’ll sell you my car for a thousand dollars,” with, “OK, I’ll give you five hundred for it,” is not a valid acceptance, because the terms of the acceptance conflict with the terms of the offer. (The response would be a counteroffer rather than an acceptance.)

Historically, courts followed the “mirror image” rule: if the acceptance varied in any way from the offer, it was not valid. Modernly, minor variations will not invalidate the acceptance.

Accord with the procedural requirements of the offer: If the offer states a particular way that the offer must be accepted, then any other method of acceptance is invalid.

Acceptance by performance: If I say, “I’ll pay you a hundred dollars if you mow my lawn tomorrow,” and you say nothing, but you do mow my lawn tomorrow, this is a valid acceptance by performance. When such acceptance is possible, but performance cannot be accomplished instantaneously, then we must examine the duties of the offeror and offeree once partial performance has begun.

Partial performance: When acceptance may be by performance, and the performance cannot be accomplished instantaneously, the offeror may not revoke the offer once performance has begun. Or, as Restatement § 45 provides, an option contract is formed. This duty of the offeror exists any time acceptance may be by performance. The duty of the offeree, on the other hand, depends on what type of contract the offeror intended to create.

Bilateral contract: If the offeror intended to create a bilateral contract (a promise in exchange for a promise), then beginning performance constitutes an implied promise. It is a valid acceptance and the offeree is obligated to finish performance.

Unilateral contract: If the offeror intended to create a unilateral contract, then acceptance is made when performance is finished. The offeree has no obligation to finish performance once they have begun. Modernly, courts will only find intention to create a unilateral contract when express language exists.

Implied-in-Fact Contract: A contract or contract term may be construed even when there are no explicit words, if there is an unambiguous offer and acceptance, mutual intent to be bound, and consideration. Courts will look to the facts and the parties’ conduct.

Rewards: An offer of a reward made to the public is an executory offer of a unilateral contract. In order to collect the reward, the person performing must have known about the offer. Such an offer may be revoked by publishing the revocation with the same notoriety as the original offer. It does not matter if the notice actually reaches one who attempts acceptance. Exception: Note that when such an offer can only be accepted by one person (e.g. there is only one lost dog to be returned), then the offeree is a unique individual who is as yet unidentified. This means that if the person who eventually becomes the offeree by completing performance, had started to perform before the revocation was made, then the revocation was ineffective.

Effective date of acceptance: An acceptance takes effect when it is dispatched to the offeror. On the telephone , dispatch and receipt of the acceptance are simultaneous. In the mail, acceptance may be dispatched within the time required by the terms of the offer, but received too late. The “mailbox rule” is that acceptance is valid upon dispatch, when the mail is an expressly or impliedly authorized method of acceptance. If one mails an acceptance, changes one’s mind, and telephones the offeror to reject the offer, the acceptance is valid even if the offeror received the rejection before the acceptance.

Knowledge of the offer: The offeree cannot accept an offer they do not know exists. In the case of rewards offered for taking certain actions, the offeree must know about the reward offer before they take the action.

Silence as acceptance: Generally, silence or inaction cannot serve as acceptance. Exception s to this are i f the offeree takes the benefit of the offer, or indicates that silence will operate as acceptance.

Only the offeree has power of acceptance: Only the offeree, as designated by the offeror, may accept the offer. If I say to you, “I’ll sell you my car for a thousand dollars,” and another person present says, “It’s a deal,” this has no effect .

Revocation: A revocation is effective when it is communicated to the offeree or the offeree learns of an act by the offeror that is wholly inconsistent with the offer, such as learning that the offeror has sold the item in question to someone else.

Rejection: When the offer is for the sale of a number of items, acceptance of one or more of them may function as a rejection of the offer to purchase the rest of them.

Power of acceptance may be terminated in five ways:

Lapse of the offer: The offer may lapse after a stated time has passed, or after a reasonable time.

Rejection: The offeree’s communication to the offeror, rejecting the offer, terminates their power of acceptance, should they later change their mind.

Counteroffer: A counteroffer always includes a rejection of the original offer. If the counteroffer is not accepted, the original offer cannot now be accepted unless it is offered again. A firm counteroffer may be distinguished from an exploration, in which the offeree wishes to explore the possibility of different terms but may still wish to accept the original offer.

Revocation: The offeror is “master of the offer” and may freely revoke it until acceptance. The revocation is only effective once it has been communicated to the offeree. This communication may be indirect, as when the offeree reliably learns, perhaps from a third party, that the offer is no longer open.

Death or mental disability of either party : No contract may be formed if either party has lost the ability to form contractual intent before acceptance.

Acceptance under the UCC has its own set of rules. First, the UCC is generally more flexible than the common law in finding agreement between contracting parties. The common law “mirror image rule” is rejected. Under the UCC, courts are more likely to find that two parties did in fact have an agreement, though the terms of the agreement are not clear.

UCC section 2-206 provides that unless otherwise stated, an offer invites acceptance in any reasonable manner; an offer to buy goods invites acceptance by promise or by shipment of conforming or non-conforming goods, except that a shipment of non-conforming goods may be offered only as an accommodation and then does not constitute an acceptance; and part performance does not constitute acceptance if the offeror is not notified within a reasonable time.

Nonconforming goods: When a buyer receives nonconforming goods and rightfully rejects them, they are entitled to damages for nondelivery. Such damages consist of the difference between contract price and market price at the time the buyer learned of the breach.

UCC 2-207 is intended to resolve situations in which a buyer and seller use standard forms that include terms that conflict with each other. The UCC, unlike the traditional common law, will find a contract. What becomes of the additional or different terms?

If either or both of the parties is not a merchant, then the terms of the offer become the terms of the contract.

If both parties are merchants, then the additional terms become part of the contract unless they materially alter it or acceptance is expressly made conditional on acceptance of the additional terms, or the offeror rejects the additional terms. If any of these situations is the case, then the additional terms do not become part of the contract and remain mere proposals for additional terms.

If both parties are merchants and there are different and contradictory terms, then they obviously cannot both become part of the contract. The “knockout rule” then applies: contradictory terms are knocked out and UCC gap fillers replace them with reasonable terms.

When printed words in a contract contradict typed or handwritten words, the typed or handwritten words are presumed to control.

At the heart of the law of contracts is the question of which promises should be enforceable by law, and central to that question is the concept of consideration. C onsideration is that thing of value, given in exchange for a promise, that makes the promise enforceable. The thing of value is usually another promise.

Not all promises are enforceable. The clearest case is a gift. If, out of the blue, your uncle promises to buy you a bicycle tomorrow, and you happily accept his offer, and then he changes his mind, you have only your own powers of persuasion to compel him to carry through. If however, your uncle promises to sell you his car for a thousand dollars, and you agree, and he changes his mind, you have the power of the law on your side, for any damages you have incurred.

Consider the ways to determine when valid consideration exists:

“A peppercorn”: Historically, any consideration would do. A promise to give away one’s kingdom was unenforceable, but a promise to “trade one’s kingdom for a peppercorn,” was enforceable. Modernly, courts are willing to examine the sufficiency of consideration.

Bargained-for exchange: Consideration is more likely to be judged to be valid if it was bargained for. Thus, a court may balk at enforcing my promise to sell my new Mercedes for one hundred dollars, but if they find that you offered to buy it for fifty dollars and I insisted you pay a hundred, the consideration will more likely be thought valid.

Benefit to the promisor or detriment to the promisee: If I say, “I will give you my car,” I have made a promise. Standing alone, the promise appears to be an unenforceable gift. If I say, “I will give you my car in exchange for a thousand dollars,” we must examine whether the promise of the thousand dollars is valid consideration, and we may do so by judging whether it is a benefit to me, the promisor, or a detriment to you, the promisee. It is both, and it is valid consideration. If I say, “I will give you my car if you will also accept this fine leather steering wheel cover,” is your promise to take the steering wheel cover a benefit to me, or a detriment to you? It is not, and it is not valid consideration, but merely another gift. If I say, “I will give you my car if you will take with you all of the old motor oil bottles in my garage,” then the promise to clean out my garage is a benefit to me and a detriment to you, and is valid consideration.

Sham consideration: “Sham consideration is no consideration.” Parties to an agreement will often attempt to make a gift enforceable by “reciting” consideration, e.g. by writing into the contract, “in consideration of $1 paid,” or similar language. Courts will generally judge this to be “sham” consideration, which is no consideration at all.

Pre-existing duty: A party’s action which he was already legally obligated to take cannot be consideration.

Contract modifications: A modification of a contract generally requires separate considerati on, though it may be merely recited. Under the UCC, no consideration is needed for a modification of a contract for the sale of goods.

Mutuality of consideration: Each party must be bound to do something, or neither is bound. Thus, each person is actually a promisor and a promisee. Looked at from this perspective, in trying to establish valid consideration, one does not seek a “benefit to the promisor or detriment to the promisee” but a “double detriment.”

Compromise: When a party agrees not to assert a cause of action that they believe in good faith they have the right to assert, in exchange for some promise or act by the other person, this may be called a compromise, and it is valid consideration.

These are theories under which promises may be found to be enforceable, outside of traditional consideration theory. It is useful to think of unjust enrichment and promissory estoppel as growing out of traditional consideration doctrine.

However, note that at common law, these theories did not exist. Therefore, if a question asks whether a promise is enforceable “at common law,” and enforcement depends on one of these theories, the answer is no.

Unjust enrichment (and its cousin, moral obligation and the material benefit rule) grow out of the “benefit to the promisor” branch of the consideration tree, while promissory estoppel grows from the “detriment to the promisee” branch. Further, unjust enrichment may be thought of as preceding consideration, and promissory estoppel following consideration, on a chronological timeline. That is, unjust enrichment (and especially the material benefit rule) may be thought of as dealing with “past consideration” and promissory estoppel may be thought of as dealing with “future consideration.” Options and firm offers deal with an intersection of offer, consideration, and promissory estoppel.

Unjust enrichment’s link to consideration is through the “benefit to the promisor” concept. Sometimes the basis of the unjust enrichment claim clearly is a benefit to the promisor, for example in a contract that is void or voidable, but unjust enrichment theory may also be applied absent a promise. It is a separate cause of action distinct from contract, but we do examine a benefit, and it is a benefit to the person who is or would have been the promisor.

An example is a doctor providing emergency services to an unconscious person, when the doctor is normally paid for such services. The patient could not agree to treatment, so there is no contract. The court proceeds under the theory of unjust enrichment, also known as quasi-contract or quantum meruit.

Unjust enrichment has two elements: injustice and enrichment (or benefit). It is not enough for a benefit to be gained, it must be unjust for it to be kept, or no cause of action arises. This is most clearly true in the case of “volunteers and intermeddlers,” that is, people who give a service without being asked and then demand payment. If you mow my lawn without being asked to, it would not be unjust for me to refuse to pay you and keep the benefit of your service.

The remedy for unjust enrichment is restitution. Restitution can also be a remedy when there is a contract that is breached, or an implied-in-fact contract. In the case of unjust enrichment, there is an implied-in-law contract or quasi-contract. The difference can affect the measure of damages. Damages for breach of an implied-in-fact contract may be based on the contract price, while damages in unjust enrichment would be based on the benefit conferred.

The doctrine of moral obligation and the material benefit rule, which is related to unjust enrichment, deals with what may be thought of as “past consideration.” Generally, “past consideration is no consideration,” which may justify our decision to place this doctrine outside the bounds of traditional consideration theory. It is easy to see why past consideration should be no consideration. Can I give you a gift, free and clear, and then later claim that you owe me something for it? I cannot.

The material benefit rule, however, allows past consideration to make a subsequent promise enforceable, so long as there is found to be a moral obligation to fulfill the promise. There is still technically no consideration. There are three elements:

The doctrine is most clearly accepted when a debtor promises to pay a preexisting unenforceable legal debt, such as a debt discharged in bankruptcy or barred by a statute of limitations. It may also be used in other cases where the three elements are met, including: a promise to perform a voidable duty, a promise to pay for a benefit previously received, and a promise to pay the debt of another (guaranty).

Promissory estoppel is a doctrine that applies when a gratuitous promise is made, and the promisee reasonably and foreseeably relies on it to their detriment. In this, it is very clearly linked to traditional consideration doctrine, in that ordinary consideration may also include detrimental reliance on the part of the promisee. The difference is that promissory estoppel applies in cases where there is no bargained-for exchange.

It should be clear why promissory estoppel is a worthwhile doctrine and resides firmly in the realm of contracts law (not tort law as some authors argue): a central principle of contracts is that promises should be enforced when they induce reasonable expectations. Promissory estoppel deals with precisely that.

The general rule is that a promise may be enforced, even absent consideration, if:

Pledges to donate to charities: Some courts have tried to enforce charitable subscriptions through consideration or promissory estoppel theory. The Restatement § 90 simply provides that a charitable subscription is enforceable without proof of reliance.

Offers are generally freely revocable until accepted. However, an offeror may promise not to revoke an offer for a period of time. If this promise is supported by consideration, then it is a valid option contract. Courts are much less likely to examine whether the consideration is sham or nominal in the case of option contracts. A mere recitation of consideration will likely suffice.

Promissory estoppel intersects with offer in the world of construction bidding and subcontracting. When subcontractors submit bids to a general contractor, they are extending an offer to do some work for some amount of money, should the general contractor’s bid to the developer be accepted. Under the rules of offers and option contracts, the subcontractor’s bid should be fully revocable until it is accepted. However, the general contractor must rely on the subcontractors’ bids in making his own bid. This detrimental reliance serves to make the subcontractor’s bid irrevocable – in effect creating an option contract, even though consideration is absent.

An offer by a merchant to buy or sell goods in a signed writing which by its terms gives assurance that it will be held open is not revocable, for lack of consideration, during the time stated or if no time is stated for a reasonable time, but in no event may such period of irrevocability exceed three months; but any such term of assurance on a form supplied by the offeree must be separately signed by the offeror.

Under common law, the pre-existing duty rule is applied, and a modification to a contract must have its own consideration, though it may be merely recited. However, beware of situations where a (seemingly gratuitous) agreement to extend the time for payment of a debt with annual interest is actually supported by the consideration of the additional interest. In addition, a modification to a contract may become enforceable if it would be fair in light of unanticipated circumstances. And under the UCC, the pre-existing duty rule is not applied and an agreement can be modified with no consideration if it is made in good faith and does not violate any clause stating that no oral modifications are permitted.

Contract defenses are arguments that a party may raise to avoid enforcement of a contract, or theories that courts may apply to invalidate a contract. Arguing a defense to formation means arguing that a proper contract was never formed. We distinguish these defenses from breach and from excuse, which are discussed in separate sections.

If a proper contract was never formed, the contract is either void or voidable. A void contract is no contract at all, but a legal nullity, and it cannot be enforced by either party. A voidable contract may be invalidated by the aggrieved party, or the aggrieved party may choose to keep the contract in force.

Mnemonic: “F luid MVP”

Mnemonic: “Duff swim”

Certain types of misrepresentation can make a contract void or voidable.

Misrepresentation: A false statement of fact. Misrepresentation of opinion is not actionable. Misrepresentation is also a tort.

Scienter: Misrepresentation made with the knowledge that it is untrue.

Fraud: Scienter made with the intent to mislead the other party. May be an express statement, deliberate concealment of a fact, or sometimes a failure to disclose a fact. When fraud is used to induce a contract, the contract is voidable.

Fraud in the factum (void): If the fraud consists of misrepresenting the actual existence of the subject matter of the contract, then the contract is void. An example would be selling a piece of property that does not exist.

Fraud in the inducement (voidable): If the fraud consists of misrepresenting the facts in order to induce assent to the contract, then the contract is voidable.

Knowledge of falsity: This may include lying or reckless indifference to the truth.

Three types of misrepresentation:

Damages for fraud: Damages may include rescission (releasing the parties from performance) as well as restitution for any unjust enrichment, if there has been partial performance. In some cases, punitive damages may be available. Although punitive damages are usually not available in contracts law, fraudulent misrepresentation is also a tort.

No one may contract to perform an illegal act. Such contracts are void. Performing work without a license when such license is required by law is held to be illegal. Thus, an unlicensed plumber may not recover payment in contract, or even in quasi-contract. An innocent party may recover in quasi-contract, but if both parties know of the illegality of their contract, the courts will not enforce recovery of any benefits gained by either party, but will leave the parties as it found them.

Courts may refuse to enforce a contract, declaring it void, when the terms are unconscionable based on the mores and practices of the community, when the terms are unreasonably favorable to one party, or when there is an absence of meaningful choice on the part of one party in entering the contract. The injustice must be such as to “shock the conscience” of the court.

This doctrine is often applied in the case of contracts of adhesion. A contract of adhesion is a boilerplate “take it or leave it” contract that one party offers to another, with little or no opportunity for negotiation. A court may void an unconscionable part of a contract, leaving the rest enforceable.

The UCC section 2-302 deals with unconscionable contracts and clauses and does not differ significantly from common law rules.

A contract is illusory if one of the party’s promises is illusory. This may be thought of as another type of lack of consideration. An illusory promise is one that does not actually obligate the party to do anything, e.g. “I’ll pay you if I feel like it.”

Duress: Compulsion of a manifestation of assent by force or threat. It may be actual physical force or threat of future adverse consequences. The threat may be of physical violence to the other party or a loved one, or may be a threat of economic harm or harm to a significant interest that cannot be measured in economic terms. The pressure must have been applied by one of the parties; the economic pressure of the marketplace does not constitute duress. Merely taking advantage of another’s economic need generally is not duress.

Extreme physical duress makes a contract void; lesser duress makes it voidable.

Third party duress may make a contract void in the case of extreme physical duress.

Misunderstanding is when parties attach materially different meanings to contract terms. Parol evidence is admissible to determine whether there is a misunderstanding. The court will find that, appearances to the contrary, the parties did not form a contract. The contract is void. The objective trumps the subjective. An example of misrepresentation is a contract where the price was agreed upon as “fifty-six twenty.” One party understood it to mean $56.20 and the other party thought $5,620.00.

Courts may invalidate a contract if the obligation of one of the parties is so vague or ambiguous that it is impossible for the court to determine what enforcement would entail. In many circumstances, especially when the sale of goods is involved and the UCC governs, reasonable terms may be filled in by gap filler provisions. Quantity is the most important term to be present in order for a contract to be valid; if the quantity is not clear and definite, the contract will likely be void for vagueness.

In the absence of illegality, courts may still declare a contract void, choosing not to enforce it based on public policy concerns. One contract that is susceptible to this defense is a covenant not to compete. Such covenants may be employment contracts or sales of land, in which the employer or seller obtains an agreement from the employee or buyer that they won’t open a competing business. A court may void such a contract if it is unreasonable in terms of time limitation, geographic limitation, or legitimate business need.

Courts may make a contract voidable when one party abuses its power in a relationship of submissiveness or trust, but actual fraud or duress cannot be pinpointed.

Courts will not enforce a contract when it is “clearly” made in jest. Whether a contract is clearly a joke will be a judgment based on what the court thinks is reasonable.

For certain types of contracts, there must be a writing signed by the party against whom the contract is being enforced, and the writing must include the substance of the agreement. If such a writing does not exist, the contract is voidable at the option of the party that did not sign. That party may void the contract by raising the statute of frauds as an affirmative defense. The six types are:

Mnemonic: “Gospel”

The clearest way to do the analysis is in two steps: 1. Is the contract within the statute (i.e. does one of the above situations apply)? If not, your analysis is over; the contract is not affected by the statute. If it is within the statute, then: 2. Is there a writing signed by the party to be bound and containing the substance of the contract’s terms? If so, the contract will not be found voidable on this basis. If not, it will.

There are a few things to remember about each of the three most common situations.

Goods $500+: The sale of goods is governed by the UCC, which has its own statute of frauds, section 2-201, which states that “a contract for the sale of goods for the price of $500 or more is not enforceable by way of action or defense unless there is some writing sufficient to indicate that a contract for sale has been made between the parties and signed by the party against whom enforcemeent is sought.” The price set by the contract is determinative, regardless of the actual value of the goods.

Exceptions are if the party to be bound admits the existence of a contract, or has paid for the goods, or if the goods are specially manufactured and partial performance has begun.

In addition, if both parties are merchants, then a signed writing by one party that is not objected to by the other party is sufficient.

The UCC treats a modification of a contract as a new contract. For this reason, if the new contract falls within the statute of frauds, it must be in writing. This is true if the original contract was for sale of goods less than $500, but the modification would make it $500 or more.

Services contracts not able to be performed within one year: Note that if the contract could possibly be performed within one year, it is not within the statute. A contract for a “lifetime supply” of a service is not within the statute, because the person could die within a year. Performance of a specific task is not within the statute because with unlimited resources, anything could be done within a year. A contract to perform a specific one-day service on a specific date thirteen months in the future is within the statute.

A five year lease that may be terminated at some time prior to one year, is not capable of being performed within one year, under the majority view, because termination is not the same as performance. Statute of frauds applies.

Land sales: This includes any transfer of an interest in land. This could technically include a lease, but only one for longer than a year. One limited exception to the statute of frauds is the “part performance doctrine,” whereby a contract may be found to be valid, even if it violates the statute of frauds, if the conduct of the parties provides proof of the existence of a contract, for instance partial payment, partial occupation of the land, or partial improvement of the land.

As detailed in Excuse of Conditions under Conditions and Promises below, a condition may be waived by the party whom the condition is intended to protect. If the condition waived is so material as to constitute the whole of the other party’s obligations under the contract, then there is no consideration and no contract.

A person who lacks capacity to contract may avoid enforcement of a contract. There are two categories: minors, and those lacking mental capacity.

Generally, a minor may avoid enforcement of a contract simply by showing that they were a minor at the time the contract was entered into. The contract is voidable at the minor’s option. They may enforce it if they wish.

If the minor chooses to avoid the contract and the (adult) they contracted with has given them a benefit, the adult may recover for the value of the benefit they gave in quasi-contract.

If the minor chooses to disaffirm the contract, they may recover against the other party for restitution damages, which will be offset by the reasonable value of any benefit they received.

A mentally incompetent person’s interest in avoiding a contract may be balanced against the other party’s justifiable reliance. The court will weigh the degree and seriousness of the mental incompetence against the degree to which the other party engaged in exploitation or improper conduct.

Intoxication can be a valid defense if the following conditions are met: the promisor was truly impaired, the promisee knew of the impairment, and the promisor made a timely effort to annul the contract.

Mistake: The doctrine of mistake can be grounds for rescission of a contract when one or more parties makes a mistake about the factual circumstances underlying the contract. The following elements must be met:

There are two types of mistake:

Mutual mistake: Both parties make the mistake. The aggrieved party may rescind, provided they did not bear the risk of the mistake. Remember the “ostrich rule”: conscious ignorance on the part of one party eliminates the “shared” aspect of the mistake; this is implicitly assuming the risk of the mistake.

Unilateral mistake: One party makes a mistake. It is more difficult for the mistaken party to get rescission. In addition to the above elements of mistake, the mistaken party must show that either:

If the non-mistaken party detrimentally relied upon the mistaken party’s promise, then the mistaken party may not avoid the contract unless the non-mistaken party knew or should have known of the mistake. (Contractor-subcontractor example: Drennan v. Star Paving.)

Courts may need to interpret or construe contract terms where the original terms of the contract are missing, or are unclear or ambiguous. Rather than declare a contract void for vagueness, courts will facilitate commerce by holding the contract valid with the additional interpretation or construction.

Interpretation: The process of discerning the meaning of ambiguous contract terms.

Construction: The process of adding contract terms by legal implication.

Courts will interpret and construe contract terms using both the subjective theory of contracts and the objective theory. Under the subjective theory, courts focus on the actual intent of the parties and what they understood each other’s intent to be. Under the objective theory, courts focus on what a reasonable party would have expected under the circumstances.

The Restatement sections 202 and 203 set forth guidelines for contract interpretation.

Restatement § 202: Rules in Aid of Interpretation:

Restatement § 203: Standards of Preference in Interpretation:

The UCC section 2-208 is similar to the Restatement rules.

Contract of adhesion doctrine: where there is unequal bargaining power between the parties so that one party controls all of the terms and offers the contract on a take-it-or-leave-it basis, the contract will be strictly construed against the party who drafted it.

Gap fillers: Standard contract provisions that courts will fill in when parties have manifested an intent to be bound but have not agreed on all the terms. Often the courts will fill in a missing term with a reasonable term. Factors in determining reasonableness may include: conventional understanding in the community, promotion of efficiency in contracts, and societal goals. The UCC gap fillers will supply a “reasonable” value for missing terms, including price, place of delivery, time for shipment and time for payment. If place of delivery is not specified then the UCC gap filler provision will provide that the buyer picks up the goods at the seller’s place of business, or the seller’s home.

Good faith and fair dealing: Beyond specific gap fillers, courts may enforce a general obligation to act in good faith. This “term” is added to the contract by implication. This obligation may be enforced even when the contract terms are clear and unambiguous, and there are no missing terms. (E.g., the dissent in “Saucy Sisters”: even though the contract could be terminated “without cause,” for United to do so simply to make a better deal was bad faith.)

There is always an implied agreement that a party will not willfully prevent the performance of a condition to their obligation.

Purposeful ambiguity: A offers to sell B “my house on Main Street.” B accepts. A owns two houses on Main Street, but B only knew that A owned one of them. A valid contract has been formed for the house that B knew that A owned. A used a patently ambiguous term as to their own understanding. B is not guilty of such negligence (or intent). Therefore, credence is given to B’s construction of the term.

There are three types of warranties for goods:

Express warranty: An express warranty need not be in writing, but may arise when part of the basis of the bargain is based on the seller making an affirmation of fact, a promise, or a description, sample or model of the goods.

Implied warranty of merchantability (UCC 2-314): Unless the parties take some action to eliminate the warranty, like including an “as is” clause, the warranty automatically becomes part of every contract for the sale of goods. The warranty only applies when the seller is a merchant with respect to goods of that kind. It states that goods must be fit for their ordinary purposes, including packaging and conformity with any label on the container.

Implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose (UCC 2-315):If the seller has reason to know that the buyer requires goods for a particular purpose and is relying on the seller to furnish suitable goods, a warranty may exist unless it is disclaimed conspicuously and in writing.

The parol evidence rule is a misnomer on two counts. First, parol evidence is defined as oral evidence, but the parol evidence rule applies to oral and written evidence extrinsic to a contract. Second, the rule is not only a rule of evidence, but a guide in interpretation and construction.

The parol evidence rule prohibits the introduction of extrinsic evidence of prior or contemporaneous agreements offered to contradict, vary, or modify an unambiguous writing which the parties intended to be a full and final expression of their agreement. Oral agreements made before or contemporaneously with the execution of the writing and written agreements made before the writing, are considered questionable, especially if they contradict the written contract. Courts may refuse to admit this evidence, keeping it from the factfinder.

Note that oral and written agreements made after the formation of the contract are not covered by the rule, because they can be considered new contracts or modifications of the original contract. Note that written agreements made contemporaneously with the original contract are not covered by the rule, because they can constitute part of the contract itself.

The parol evidence rule was once applied strictly: if a written contract was clear on its face, with no obvious omissions (“fully integrated”), then a judge would not even consider the content of evidence covered by the rule. Modernly, the rule has ceased to be a rule of evidence and is more of a guideline in analyzing such evidence. A modern court would consider the content of the extrinsic evidence in determining both whether it should be admitted at all and to what degree it should be allowed to influence the interpretation of the contract.

These two approaches to the rule are played out in Mitchell v. Lath. A buyer of real estate alleged that the seller had agreed orally to remove an unsightly icehouse, but the written contract did not mention this agreement. The majority held, under the strict, classical view, that because the written agreement appeared complete, the extrinsic evidence could not be considered at all. The dissent argued that the nature and content of the extrinsic evidence should be taken into account in deciding whether to admit the evidence, and how such evidence should guide interpretation. The dissent asked: How can the written agreement be complete if it excludes a term the parties agreed to?

To eliminate these kinds of disputes, parties may include a term saying that the present writing is the full integration.

Conditions and promises are two types of contract terms that are important in determining the obligations of parties to a contract. In determining these obligations, it may be necessary to define whether a term is a condition or a promise, and what type, which is not always made clear by the written agreement. This determination may be thought of as part of the process of interpretation and construction. Note that a term of the contract need not be either a condition or a promise. It may be, e.g., a definition.

Condition: An event that creates, limits, or discharges an obligation.

Promise: An obligation.

Condition precedent: A condition that creates a future obligation.

Conditions concurrent: Simultaneous conditions that create simultaneous obligations.

Condition subsequent: A condition that negates a preexisting obligation.

Note that the distinction between conditions precedent and conditions subsequent is a fine one. The exact same change in obligation may be a condition precedent or a condition subsequent depending on wording. For example, if our contract states, “If it doesn’t rain tomorrow, you must wash my car,” a lack of rain tomorrow is the condition precedent to your obligation to wash my car. If our contract states, “If it rains tomorrow, you are released from your obligation to wash my car,” then the rain tomorrow is a condition subsequent to your release from your obligation to wash my car. The distinction is only important in determining parties’ burden of evidence. Assuming you failed to wash my car, in the former case, I would have the burden of proving that it didn’t rain. In the latter case, you would have the burden of proving that it did rain.

Express condition: A contract term that is articulated as a condition through the use of “conditional language,” such as “conditional upon,” “subject to,” “provided that,” etc. A statement like, “Seller will provide a steering wheel cover” is less likely to be interpreted as a condition than, “Buyer’s obligations are conditional upon Seller’s providing a steering wheel cover.”

Implied condition: A condition inferred by the court from the facts of the case; based on the intent of the parties.

Constructive condition: A condition created by the court as a matter of law; based on public policy principles.

Pure condition: An event that creates an obligation but is not itself an obligation.

Promissory condition: An obligation that, when satisfied, creates another obligation.

Pure promise: An obligation that does not create another obligation.

To illustrate the differences among the above, assume that a contract states, “If it doesn’t rain tomorrow, you agree to wash my car. If you wash my car, I agree to pay you fifty dollars.” A lack of rain tomorrow is a pure condition. You washing my car is a promissory condition. Me paying you fifty dollars is a pure promise.

Under some circumstances, an express condition may be excused.

A waiver is a knowing and voluntary abandonment of a right. It may be made expressly or impliedly. It is one-sided, without anything being received in exchange. If something were received in exchange, consideration would be present and the change would constitute a modification contract. If the right is material, the non-waiving party may not raise waiver as an excuse.

Estoppel comes up when a party waives or abandons a right (it need not be voluntary, it may be careless), and the other party relies on the abandonment to their detriment. The abandoning party is estopped from exercising the condition.

Performance of a condition may be excused if the other party engages in obstructive or uncooperative conduct. This has the effect of making the obligations of the obstructive party unconditional.

Courts may choose to excuse performance of a condition if it would result in an unfair forfeiture on the part of the party to perform.

Burdens of proof: Generally, the plaintiff has the burden of pleading and proving that all conditions precedent and concurrent with the ripening of defendant’s duty of performance have either been performed or excused. Once this is established, if defendant wishes to rely on the escape possibility provided by any conditions subsequent, they have the burden of alleging and proving the happening of the event that satisfied the condition subsequent as an affirmative defense.

The doctrine of breach arises when one party is alleged to have failed to perform its obligations under a contract. The court will determine whether the party alleged to have breached has committed a material breach or has substantially performed. To determine that a party has materially breached is to determine that it has not substantially performed.

The determination is important because if the breaching party has substantially performed, they may enforce the contract, holding the non-breaching party to their performance (usually payment), minus any allowance for the economic loss of the breach. In contrast, if the breach is material, the breaching party has no claim to damages under the contract. They may only pursue a limited claim under unjust enrichment for the benefits conferred by their part performance.

Damages: Note that in order to find for a party claiming breach of contract, there must be damages. A court may find that there was a breach, but no damages, and so the breaching party owes nothing.

Material breach: A substantial violation of a contractual obligation, such that the non-breaching party does not receive a substantial benefit of the bargain. This usually excuses the aggrieved party from further performance and affords it the right to sue for damages.

Substantial performance: Performance of the primary, necessary terms of an agreement; contract continues with further performance, some damages may be awarded.

Factors in determining whether a breach is material: Different authorities present slightly differing lists of factors in determining whether a breach is material. Therefore, consider this a list of some factors that may be used.

Mnemonic: “Halt Wage” (Think of an employer halting wages as a material breach.)

Divisibility: If both parties intended to separate the contract into a series of contracts that may be thought of as standing alone, then a breach of one part may be interpreted to not constitute breach of the whole, allowing the breaching party to keep the non-breached parts of the contract in force.

Breach under the UCC: The UCC has its own rules for breach that apply to sales of goods. The important difference is that historically, under the perfect tender rule, any breach is a material breach. Modernly, courts have interpreted the rule as applying only to “substantial” breaches.

UCC Perfect Tender Rule: If goods fail in any substantial respect to conform to the contract, the buyer may reject them. This constitutes breach, unless the defect is cured. To determine substantiality, the UCC looks to trade usage, course of dealing, and course of performance.

Cure: When non-conforming goods are rejected by the buyer, the seller has the right to cure the defect by sending conforming goods within the time for performance, provided they seasonably notify the buyer of their intent to cure.

Notice of breach: If the buyer accepts the goods, they may no longer reject them, but if a breach is discovered, the buyer must notify the seller of breach within a reasonable time or be barred from any remedy.

Installment contracts: An installment contract is a contract calling for separate deliveries. The right to reject is limited. The buyer may reject an installment only if it substantially impairs the value of that installment and cannot be cured. In addition, the buyer may cancel the whole contract if a defect in one installment substantially impairs the value of the whole contract.

Identification: Under the UCC, even when goods are non-conforming and the buyer has the right to return or reject them, the buyer obtains an insurable property interest in the goods by identifying them as goods to which the contract refers. Identification may occur by agreement of the parties, when the contract is made if it is for the sale of goods already identified, or in the case of a contract for the sale of future goods, when the goods are shipped or marked by the seller.

Risk of loss: Under the UCC, in the absence of breach, when the goods are to be delivered by carrier to a particular destination, the risk passes to the buyer when the goods are duly tendered at the destination. If there is no particular destination, the risk passes when the goods are delivered to the carrier. If the goods are held by a bailee to be delivered without being moved, the risk passes when the buyer receives title or acknowledgment by the bailee of the buyer’s right to possession. In the case of breach, the risk of loss remains on the seller until cure or acceptance.

Anticipatory repudiation: Repudiation of a contractual duty before the time for performance gives the injured party an immediate right to damages, creates their obligation to mitigate any further damages, and discharges their remaining duties of performance. The breaching party must have made it clear by their actions or statements that they do not intend to perform. The reason a party may wish to repudiate is if they know they will be unable to perform and they want to force the non-breaching party to mitigate damages. Anticipatory repudiation does not apply when the non-breaching party has fully performed.

Materiality: The anticipated breach, of course, must be either material, or constitute substantial performance. If it is material (or “total”), then anticipatory repudiation excuses the non-breaching party from further performance and gives them the right to sue immediately for damages based on the entire contract. If, on the other hand, the breaching party has substantially performed, then the aggrieved party is not relieved from performing, but may still sue for damages based on the partial breach.

Words: The breaching party may make it clear by their own statement that they intend to breach. The statement must make it “quite clear” that breach will occur; vague doubts about ability to perform will not do. However, expression of vague doubts may allow the non-breaching party to request reasonable assurances and suspend performance until assurances are received; the failure to give them will constitute repudiation.

Action: The breaching party may also make their intention to breach clear by their actions. In this case, the non-breaching party may sue for damages immediately. However, the action must be voluntary, and must make it clear that performance will be impossible, or that there is a prospective inability to perform.

Retraction: After the breaching party has repudiated, they may still retract the repudiation before the time of performance, as long as the non-breaching party has not materially altered their position, sued for breach, or stated that they regard the repudiation as final.

Prospective inability to perform: A party may, instead of fully repudiating a contract, give notice that although they would like to perform, they may be unable to. The other party may be unsure whether a repudiation has occurred and whether they still have a duty to perform or now have a duty to mitigate damages. If they have reasonable grounds for insecurity about performance, they may make a demand for adequate assurance of performance. If there is an inadequate response, this may be treated as a repudiation.

The three types of excuse due to changed circumstances are concerned not with facts in existence when the parties enter into the contract (that would be treated as the defense of mistake), but with new facts that arise after the contract has been formed. Each of these excuse the performance of a party because supervening events not of the parties’ making make the original purpose of the contract impossible or impracticable to carry out, or frustrate the original purpose. These doctrines are closely interrelated, and are thought of by some courts as falling under a general label of impracticability.

When this type of excuse is applied, the parties are excused from continued performance, and restitution or reliance damages are available.

Impossibility: The contract performance cannot be carried out (e.g. supervening illegality, supervening destruction, or death or incapacitating illness of a party). Note: if the conditions that made performance impossible were foreseeable at the time the contract was made, then they will be deemed to have taken those conditions into account at the time they made the contract. The likelihood that one of the parties may become too sick to perform is usually deemed to be foreseeable.

Impracticability: The contract performance is too burdensome to carry out, which must be subjectively and objectively impracticable. The aggrieved party’s belief that performance would be impracticable is insufficient; the courts will decide if it is reasonable to require performance. When for example a supplier cuts off supplies that a party needs in order to perform, and both parties assumed that would not happen, impracticability may be found.

Frustration of purpose: The contract performance can be carried out but it would not serve the original purpose of the contract. Both parties must have a shared understanding of what the original purpose of the contract was. (Coronation example: Krell v. Henry.) Courts will examine the foreseeability of the supervening events (for instance whether the risk was allocated to a party) and the totality of the destruction of the purpose.

If there is an unconditional duty or any conditions have been satisfied or excused, then there is an immediate duty to perform and that duty must be discharged. Note that there is some overlap between defenses to formation and ways a duty may be discharged, for example with illegality. The difference is that if the purpose of the contract was illegal at the time the contract was made, then it is void. In the case of supervening illegality, where the activity became illegal after the contract was formed, then there is a contract and a duty that is discharged.

Mnemonic: “A Criminal’s Crops”

(Think of a contractual duty to grow a crop discharged because the crop was made illegal.)

Contract remedies operate on a compensation principle: they seek to make the aggrieved party whole. Thus, contract damages are compensatory damages. There are no punitive damages in contract disputes, except where there is also a tort involved. Judicial remedies serve to protect one or more of the following interests of promisees: their expectation interest, reliance interest, or restitution interest.

In protecting the promisee’s expectation interest, courts will seek to put the non-breaching party in a position as if the contract was performed. Assuming money damages, the amount is measured by the loss in value to the injured party caused by the failure of the failing party, plus consequential and incidental damages, minus any costs they avoided by not having to perform. Though the measurement is of losses to the injured party, they must be objectively reasonable. The measurement may refer to the market value of the performance, or to a substitute transaction.

Within the category of the expectation interest, there are three types of damages:

Direct damages: Damages that naturally flow from the breach of contract.

Consequential damages: Damages that are the consequence of breach of contract, i.e. loss of profits, damage to property, etc. Breaching party will be liable for reasonably foreseeable consequences of the breach.

Incidental damages: Costs incurred in coping with the breach of contract, i.e. arranging for alternative performance, etc.

There are several tests for the validity of damages, or limitations on recovery:

Causation: The damages must have been caused by the breach.

Reasonable certainty: The damages must be reasonably certain.

Foreseeability: The consequential damages must be foreseeable. E.g. I failed to repair your car on time and so you missed a meeting where you were going to seal an important business deal. The key is whether you informed me of the importance of the timing when we contracted: this is what makes the damages foreseeable.

Mitigation: Post-breach (or post-anticipatory repudiation), the non-breaching party has a duty to mitigate damages to a reasonable degree. Damages that result from the non-breaching party’s failure to mitigate are not recoverable.

Much of the doctrine of remedies is the same under the UCC as under the common law. Obtaining substitute goods is called “covering.”

A liquidated damages clause in a contract makes certain (“liquidates”) the amount of damages in case of breach; this is done because it is expected that damages would be difficult to calculate. For the clause to be enforceable, the amount must be reasonable in light of the anticipated or actual loss caused by breach and the difficulties of proof of loss. A term fixing unreasonably large liquidated damages is unenforceable because it would constitute punitive damages. Traditionally, only the estimated loss at the time the contract was entered into was considered in deciding reasonableness; modernly the actual damages are considered. Traditionally, the rule that damages had to be difficult to calculate at the time the contract was entered into was a strict one; modernly, it may be understood to be one aspect of judging the reasonableness of the clause in light of the anticipated loss.

Rescission: Rescission allows a party to disaffirm a contract. This is logically separate from damages based on breach of contract, in which the aggrieved party would be seeking to affirm the contract. Rescission must be based on some defect with the contract, such as material breach, lack of consideration, fraud, or undue influence. In the case of illegality, duress, or mistake, rescission is the only remedy; a party may not sue for breach based on these defects, but must either take the contract as is, or rescind. Often a party will couple rescission with restitution, seeking to disaffirm the contract and obtain damages for value already transferred. In the case of mutual rescission, both parties may agree to rescind a bilateral contract.

Reformation: When a written contract does not reflect the actual agreement between the parties, for example because of an inadvertent typographical mistake or “scrivener’s error,” the court may reform the contract so that it accurately describes the true agreement.

In most cases, the appropriate remedy is legal damages. For courts to apply an equitable remedy such as specific performance or an injunction, the remedy at law (payment of money) must be inadequate. This would be the case when the contract was for something unique such as real estate or an antique object. The court could then order specific performance or issue an injunction, ordering the defendant to perform, which could be enforced by the threat of imprisonment for contempt of court.

Specific performance: When money damages would be inadequate to compensate the aggrieved party, the court may order specific performance, compelling the defendant to transfer ownership of property, or accomplishing the transfer by court order.

Injunction: Compelling a defendant to perform a services contract is not as easy to enforce, and the Thirteenth Amendment prohibits involuntary servitude. Therefore, instead of ordering a defendant to perform, a court may instead enjoin them from certain other actions, such as working for plaintiff’s competitors. Courts may also issue temporary restraining orders or preliminary injunctions to maintain the status quo, for instance to restrain the defendant from conveying real property to a third party while the plaintiff’s action for specific performance is pending.

Replevin: Replevin is specific performance for goods. The buyer may replevy unique goods from the seller in certain circumstances, such as when the buyer has been unable to obtain substitute goods.

Constructive trust: An equitable restitutionary remedy forcing a defendant to convey title to property unjustly held.

Equitable lien: Defendant may have a lien imposed on their property because of a debt owed to plaintiff.

If an equitable remedy is sought, equitable defenses apply, in addition to regular contract defenses.

Laches: The plaintiff delayed bringing an action and this prejudiced the defendant.

Unclean hands: The plaintiff is guilty of wrongdoing in the transaction in question.

Hardship: Hardship applies as a defense if the consideration was grossly inadequate, the contract was unconscionable, or “sharp practices” were used. A court may also balance the hardship to the defendant or the public if specific performance were granted against the harm to the plaintiff if it were not.

Mistake or misrepresentation: If the mistake or misrepresentation would be grounds for rescission or creates a hardship, this is a valid equitable defense.

Sale to bona fide purchaser: The defendant purchased in good faith.

Reliance interest: In promissory estoppel or in breach of contract, the promisee is reimbursed for the expenses they incurred in reliance on the promise. Another way to look at it is that the non-breaching party is put back in the position they would be in if the contract was never entered into. In breach of contract, reliance damages are used when expectation damages are too difficult to calculate. Reliance damages can be essential (direct) or incidental (costs incurred in preparing to take advantage of a benefit expected under the contract). Only essential damages can be recovered traditionally; modernly reasonable incidental damages are permitted.

Restitution interest: In unjust enrichment or quasi-contract, the party that was not unjustly enriched is reimbursed for value conferred to the party that was unjustly enriched. In breach of contract, if the aggrieved party is unable to calculate what its expectation or reliance damages would be, they may only be entitled to restitution damages. In addition, in some circumstances of breach, the benefit conferred on the breaching party may be more than the expectation damages, so the non-breaching party would seek restitution damages. Restitution is measured by market value. Direct damages only.

In the past, at common law a breaching party may not have been able to recover anything. Now, the breaching party may also have remedial rights.

Restitution for the breaching party: It is now recognized that even though the breaching party is at fault, preventing recovery for the breaching party would create a forfeiture for them and a windfall for the non-breaching party. Therefore, restitution may be available for any part performance before the breach. The remedy would have to be restitution for unjust enrichment, not breach of contract, because the party seeking the remedy is the one in breach and cannot show a breach by the other party. In the case of a services contract, where the breaching party accomplished a significant amount of work but then failed to finish the job, they may not recover the contract price, but they may recover restitution of the value of the benefit conferred to the purchaser of the service. In the case of a contract to purchase goods or land where installment payments have been made but then the buyer cannot complete payments, they may be entitled to the return of some of the payments.

Sometimes parties other than the original contracting parties have enforceable rights or duties under a contract.

After a contract is formed, one party (assignor) may assign their rights under the contract to a third party (assignee), who now has contract rights against the other original party (promisor or obligor). When a right is assigned, the assignor no longer has the right. Most rights are assignable, but there are exceptions. A contract can contain terms limiting or prohibiting assignment. In addition, if the assignment would materially change the obligor’s circumstances, assignment is not permitted. Rights to certain personal services cannot be assigned.

When a contract prohibits assignments, any assignment actually made is still valid and the assignor is liable for breach of the agreement not to assign. The right to assign has been given up, but not the power to assign. Assignments may be oral. Major exception: assignments of land or interests in land: statute of frauds applies.

Gratuitous oral assignments are freely revocable. Gratuitous written assignments may be irrevocable.

If no contract presently exists, no assignment can be made. However, a promise to assign one’s rights under a future contract, if and when such contract is formed, may still be enforceable: courts may impress a constructive trust on the proceeds from whatever rights were attempted to be assigned.

Homeowner’s insurance is usually not assignable when a homeowner sells their home, because the insurer’s risks may change depending on who the buyer is.

A contract to buy real estate, when it is contingent on a future mortgage, may not be assigned by the party who will attempt to secure the mortgage, because the other party cannot be forced to accept the assignee’s credit risk.

Scholarships are usually not assignable.

Before the obligor learns of an assignment by the obligee, if an obligor and obligee agree in a commercially reasonable manner to a valid modification of the contract, the modification is effective as to the rights which the assignee has acquired against the obligor. An assignment confers upon the assignee whatever rights the assignor had at the moment of assignment, and only those rights. Thus, if the obligor had any defenses against the assignor at the time of assignment, they also have them against the assignee. Although an assignment does not imply a warranty that the obligor will perform, an assignment for consideration does imply a warranty that at the time of the assignment, the obligor had no defenses.

After a contract is formed, one party (delegor) may delegate their duties under the contract to a third party (delegee). The delegor is still secondarily responsible to the original promisee for their contract duties should the delegee fail to perform. However, the delegor has recourse against the delegee for their failure to perform.

Older cases require express assent to the assumption of delegated duties, but modernly when such delegation is clearly coupled with assignment of rights, the acceptance of the assignment of the rights operates as assent to the delegation of the duty.

Under the UCC, delegation of a duty is reasonable grounds for uncertainty on the part of the party to whom the duty is owed as to whether it will be performed, entitling it to demand reasonable assurances and suspend its own performance until such assurances are received. Failure to furnish such assurances is a repudiation of the contract.

Novation: When both parties agree to a transfer of duties, the delegor is completely released from their contractual duties. A helpful example is that of a sublease. A tenant may sublease their apartment without informing their landlord, provided the lease does not prohibit this. They thereby assign their rights and delegates their duties to the subtenant. If the landlord doesn’t fix the heat, the subtenant can sue them, and the original tenant cannot. But if the subtenant doesn’t pay the rent, the landlord can sue the original tenant or the subtenant. If the landlord agreed to the transfer of rights and duties, then this novation would mean that the landlord would have to go after the subtenant for the rent, not the original tenant.

A contract may be formed between two parties for the benefit of a third party. A life insurance contract is a common contract with a third party beneficiary. Any intended third party beneficiary can enforce the contract against the promisor. If the third party is expressly named in the contract, that is the most powerful evidence that they are an intended beneficiary. If not, there is a strong but rebuttable presumption that they are not an intended beneficiary. Note that we are talking about the promisor who has made a promise that would benefit the third party.

A party is only a third party beneficiary if the contract calls for performance to be made directly to them. If two people contract and one of them intends to give a gift after performance of the contract, the intended recipient of the gift is only an incidental beneficiary of the contract and has no rights.

The general rule is that the original promisor and promisee may modify or rescind the contract, and a donee third party beneficiary has no remedy. However, once their rights have vested, or once they rely on the promise, then they have enforceable rights under the original contract.

Promissory estoppel applies to third party beneficiaries under the Restatement and the modern trend. Thus, a gratuitous promise made for the benefit of a third party which induces reasonable reliance on the part of the intended beneficiary, may be enforced as against the promisor.

Creditor-beneficiary: A third party beneficiary who is intended to benefit from a contract between two other people based on an obligation that one of them owes to the creditor-beneficiary.

Donee-beneficiary: A third party beneficiary who is intended to gratuitously benefit from a contract between two other people.

Donor-promisor: One of the two contracting parties, when a contract is for the benefit of a third party. The donee-beneficiary may enforce their rights against this party.

Donor-promisee: One of the two contracting parties, when a contract is for the benefit of a third party. The donee-beneficiary has no enforceable rights against this party.